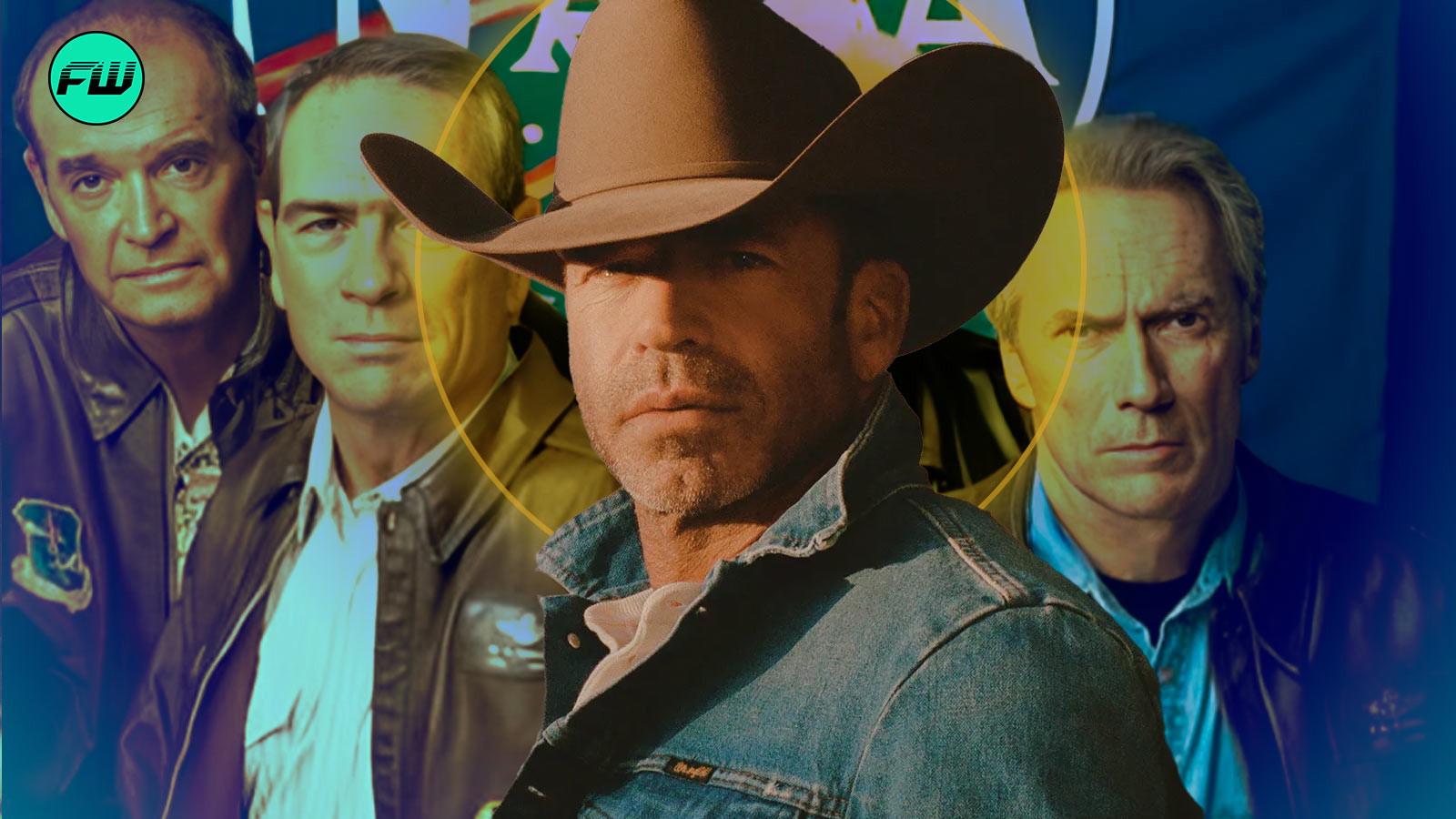

The television phenomenon Yellowstone, created by Taylor Sheridan, has been more than just a drama about the Dutton family’s trials in Montana; it has become a cultural touchstone and a statement about the resilience of the Western genre in modern entertainment. When Sheridan first developed the series, there was skepticism within Hollywood about whether Westerns could still thrive, particularly after years of the genre being considered niche, outdated, or commercially risky. Clint Eastwood, once synonymous with Western storytelling, directed a film later in his career that carried the weight of expectation but failed to resonate with audiences and critics in the way his earlier classics had. With only a middling critical reception hovering around seventy-eight percent approval, it seemed to signal the Western’s decline, reinforcing the perception that audiences were no longer interested in stories of ranches, cowboys, land disputes, and the frontier’s moral complexities. Sheridan saw this not as a death knell but as a challenge, an opportunity to modernize the genre without sacrificing its essence. His approach was radical: instead of trying to replicate the dusty, sepia-toned images of traditional Westerns, he infused Yellowstone with a contemporary energy, embedding it in current cultural, economic, and political tensions while retaining the timeless themes of family loyalty, betrayal, survival, and identity. The Dutton family’s struggles to defend their sprawling Montana ranch became a metaphor for larger battles between tradition and progress, legacy and change, morality and ruthlessness. Sheridan’s decision to focus not only on cowboys and ranch hands but also on Native American communities, corporate developers, and politicians created a narrative tapestry that reflected the ongoing clash of values in the twenty-first century. He showed that the Western could still be deeply relevant when framed around the modern American experience. What set Sheridan apart was his insistence on authenticity: the rugged landscapes were not just backdrops but living, breathing characters that shaped the story; the cattle work, horse training, and frontier skills were depicted with a realism often absent in stylized Westerns. This dedication to truth made the show resonate even with audiences who had never set foot on a ranch. Moreover, Sheridan’s characters were morally gray, layered, and contradictory, which drew viewers into the psychological intensity of the story. John Dutton, played by Kevin Costner, became both a patriarch to admire and a man whose decisions carried devastating consequences, echoing the kind of flawed hero archetypes once popularized by Eastwood himself. The irony was that Sheridan achieved what many thought impossible: he made Westerns mainstream again, even among younger audiences raised on superhero franchises and futuristic blockbusters. The ratings surge of Yellowstone and its subsequent spinoffs—1883 and 1923—proved beyond doubt that the appetite for Western narratives had never truly vanished; it simply needed to be reimagined. Sheridan himself has admitted in interviews that he writes with a chip on his shoulder, seeking to prove wrong those who doubt the strength of traditional storytelling forms. In crafting Yellowstone, he directly countered the idea that Eastwood’s later career misstep represented the end of the Western. Instead, Sheridan demonstrated that a genre is never dead if someone has the vision to reinvent it. He turned supposed obsolescence into opportunity, giving television audiences a saga that felt Shakespearean in its scope yet uniquely American in its texture. The show’s cultural impact has been profound: it sparked a tourism boom in Montana, influenced fashion with cowboy-inspired trends, reignited interest in country music and ranch lifestyles, and inspired a resurgence of frontier-set dramas across streaming platforms. Sheridan didn’t just revive the Western; he repositioned it as a vital lens through which to examine modern conflicts about land, heritage, and survival in a rapidly changing world. Looking back, the contrast between Eastwood’s film—viewed by some as the fading gasp of a once-powerful genre—and Sheridan’s Yellowstone—embraced as a blazing revival—highlights the cyclical nature of storytelling in Hollywood. One creator may falter, but another, driven by passion and vision, can reframe the narrative entirely. Sheridan made his point loudly: the Western was never dead; it was simply waiting for someone to dust off the saddle, climb back on the horse, and ride it into a new era. His success underscores that genres only die when storytellers stop challenging conventions, and with Yellowstone, Sheridan has secured his place not just as a writer and director, but as the man who brought the Western roaring back to life for a generation that didn’t even realize it was hungry for tales of the frontier.